- Home

- Caroline Gill

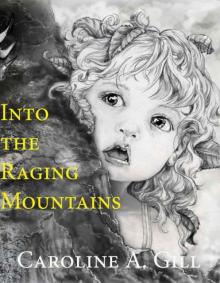

Into the Raging Mountains Page 22

Into the Raging Mountains Read online

Page 22

The moral always seemed to be that the good win, the wrong lose, and order continues. The subtle shades of gray within the range of human emotion and behavior were not easy to understand and not logical to her senses. With the implacable certainty of a six-cycle-old, Azure knew everything she needed to know. Her world was simple and finite.

*

As the growing season warmed in its course, the initial bloom of green was replaced by the spontaneous flowering of trees and the bursting open of plant buds. Riotous color filled the valley, flowing from the riverside with its lush green and splashes of vibrant yellow, crimson, and magenta petals over the valley's inhabitants, a cheering sight. Each cottage dwelling had functional vegetable plantings and herb gardens which bloomed in perfect harmony with the surrounding land. The power of that green growth, the joy of the new planting season, echoed in richness up to the sides of the partially visible mountaintops. The crops were well planted and easily growing. Life meandered on in a familiar pattern.

As the strength of the sun began to gain power and the plant life responded with such welcoming fervor, the bounty of the harvest season seemed a long way off in the distant future. Only one inhabitant knew of the harvest that was coming. Only one person had seen the deep wrong enter into the fertile field, only Roach. And no one talked to her, nor even saw her, dug in on the edge of the village, hidden under the fullness of evergreen bushes. Even if she could call the alarm, the villagers had made it clear in their actions and belligerence that her life was forfeit should she walk in the daytime. There was no way to bring them any warning.

So Roach watched, fascinated. She saw. She knew and stood witness.

*

The disappearances began one brisk nightfall in the midst of harvest, somewhere between sunfall and pure dark.

A family of foresters that lived on the scattered, ragged edge of the village was first to be taken. They would have seemed the most resourceful of the inhabitants to the unfamiliar observer.

Most sad of all, no one missed them. There was no great hue and cry, no mob to search out the culprit, no investigation by the upright and honorable village council, no notice at all. Their absence was only noted at the church services and then only in passing. It was only much, much later that their vanishing was viewed as troublesome, and then, too late to do that poor family any good.

Second to go missing was Mardint, a small wiry man known mostly for his full beard and honking laughter, and his plump wife, Tabitha. Their absence was a little more obvious. She was a satellite of one of the more unsocial women's groups, and was only known for the whistle through her teeth that occurred when she spoke, so that she constantly sounded like she was trilling along with the conversation. The whistle might have gone through her ears as well since she rarely said anything of much import and took much too long to say it.

One of the older school children from Lalayda's class, Rantha, went to their cottage every fifth day to collect eggs and take lessons on the wood flute from Tabitha, a slightly accomplished musician. Upon discovering the oddly abandoned dwelling, with windows broken and chairs upturned, the young girl had enough sense to run for home. It was her concerned mother who brought the village's attention to the missing family.

Even then, the village elders voiced their opinion that there was no cause for alarm, no cause at all. The fourth elder rose with some degree of officiousness and declared the need for an investigation, just to be certain. All agreed to send two men to the home to look for the family or some farewell note of their travels. Nothing of excitement had ever occurred in the village's remembered history. Collectively, they were fascinated by the ruckus. Still most of the sheltered villagers saw all these events as minor blips on a rather uneventful growing season.

Even nominated to go nose around someone else's abode, the very idea of intruding on a fellow villager's privacy did not set well with most of the men. Cethel was attending the meeting with his gruff father Centen and his uncle, Tomlin. When his father raised an obliging hand at the call for volunteers, Cethel was not surprised.

His father had raised him in the woods, and so had his father before him for generations of time. Capable, and indeed, mostly unflappable, they were trustworthy and honest, if a bit brusque and stiff. With a nod of acceptance, the fourth elder sat.

It was a simple task. Walking away from the town's hall, hardly working to keep stride with the two older men, Cethel asked earnestly, “Da, can I come along for the visit?”

With a pause of step and a measuring glance, Centen turned and eyed his son. No longer a boy and clearly eager to be taken at a man's worth, Cethel's eyes implored him, while his gangly body held the pose of indifference. Centen stared, measuring for a moment more, and gave one quick nod, walking on.

Elated, Cethel fell into step behind his father and uncle, listening avidly to their brief conversation, and occasional insight. They were about their assigned business with no wasted effort. Knowing the woods as they did, the three men followed the most direct path to the vacant house.

Arriving with some minor amount of stealth, they walked the perimeter, looking for signs of struggle or of travel. No one was there—no one alive certainly. The windows were broken in, and the sturdy wooden door hung ajar on crooked hinges, unbroken. The ramshackle barn behind the house was open and empty.

With his father's waved hand giving him direction, Cethel walked calmly to the main building with confidence born of youth. He easily pushed it open, and cautiously looked around the main room. It was a silent house, but the window spaces left enough lightfall that it was not gloomy. Nothing inside was glaringly amiss to his eyes. Cethel could clearly see every corner of the room. The chairs sat upright around the table, which was set with abandoned and empty dishes. He stepped to the doorway and signed to his father with an exaggerated shrug.

Tomlin brushed past him and entered the abandoned dwelling, reappearing momentarily with the same view. The people were just gone. Thinking to check the cabinet for a bit of bread, Cethel found it hardened and beginning to mold, inedible. He searched the room for the food larder. His father joined him, checking the back room briefly. With a grunt, Tomlin located the larder door, hidden under the worn and patched gray and tan braided area rug.

Pulling it open, the three men looked down into the darkness, their eyes adjusting. A small amount of food lined the walls, but no people hiding below suddenly appeared. Well then, they had completed their assignment and saw no need to stick around with work to be done for their own family. With Centen in the lead, they set off back the way they had come, returned to the village's meeting hall and gave their report to the waiting village council: the cause of the disappearances was unclear, but likely not voluntary.

As the meeting was about to disperse, the priest entered the village hall, and strode to the front. With a sonorous voice, trained to carry, he had no difficulty being heard.

“Where is my cleaning woman? Where? I have come to lodge a complaint. I cannot find her anywhere and she has left my household in filth. I must protest! It is part of my residency here that I have a clean house, a tended garden and a well-stocked larder. I cannot do these things alone, my friends! It takes all of my power, commitment, and love for your village to prepare my tenth day devotions! Does anyone know where the woman is?”

“Her name is Breina, sir. Breina.” piped up one young woman.

“Yes, Yes. Breina, it is. Her name is known, but not her location. If she cannot keep my house clean and be counted on to do just that, then I really must insist on a new keeper.”

“You say she is missing, sir? Missing how many days, sir?”

“She hasn't come for a least five days. The dishes are piling up so, they will soon fall on me. It is ridiculous to think that I can feed myself and have time to create the stirring lessons on tenth day.” Staring around the room at each elder's perplexed face, he insisted, “I waited with patience. Now I really must protest! It is time for the council to assign another her tasks,

so that I may be about my work.”

The village council did not answer. Not because they didn't want to but rather because they were at a loss of words.

A softer voice spoke out of the gathered crowd, “But, Breina did not come to my home last nightfall for supper. She always comes on seventhday for mealtime and brings me some of her relish to share.” Hair gathered tightly under her scarf, a woman stepped forward.

“You know she is my sister, and apologies to you, priest, but this is not like her. Breina has always been dutiful.” As the thought flew across her mind, Margreetha blurted it out.“What if she is missing too?” Horror bloomed on her face, as the possibility of Breina being taken forcefully finally occurred to her. Margreetha started crying into her apron.

Already at a high emotional level of nervous guardedness from the ongoing mystery of the Rat Thief, this more immediate danger lurked in their midst. A few older women's mouths started flying, offering suggestions and options, searches and directions—anything to combat the feeling of helplessness. But there was nothing to be done, no enemy to fight. How do you fight vanishings, after all?

Standing abruptly, the second elder spoke with an authority the fourth had lacked. “There is nothing to be done here for them. While it is clear that Tabitha and Mardint have been removed from their house, we do not know where they have gone or what has become of them. The best thing for us to do is to, first, protect ourselves. We must watch our neighbors and stay clear of the woods.” Looking at the other elders who nodded in agreement, he continued, “All families dwelling near the edge of the wood must pack their belongings and move into the village's center for a few days, while teams of men search the forest for signs.”

Usually there would have been a loud combination of protesting and commotion about packing up twenty or so families and making them move from their homes, but the outlying people eagerly accepted the protection of the village. Nodding their acceptance, and whispering to each other, they traveled to their homes in groups, waiting outside while the family packed quickly all the important items before moving on to the next house.

Eyes watched them, noticing.

Watched them all.

*

Azure dozed in her favorite spot, a bench piled with cushions with a view out of the largest window, high on the farthest foothill, overlooking the troubled valley. Tatanya had just finished cooking spicy squash and nut bread. The warmth of the oven and the rich smell of the dessert filled the modest house. It was a perfect growing season day, neither too hot nor too cold. There were chores to be done, always, yet there was that magical moment of calm in the later part of the daytime, when a girl needed to restore some of that constant, glowing energy.

Tatanya hummed along a repeating tune and straightened the kitchen cloths.

Chapter Twelve

No Way to Safety

Alizarin stood in shock. What can I do now? Gretsel had run from her as if she were filled with insanity, dangerous and dark. She could still hear her friend's voice as it weakened in desperation, subsiding into heart-gutting sobs.

Alizarin followed Gretsel inside the Corded Family Farmhouse, and sat outside of her door, listening to the pain and panic of her dear friend. The sobs eventually subsided, except for the occasional hiccup.

She did not dare to speak.

Wracking her brain for some way to ease the trouble of her heartsister, she found none. A few moments of silence passed, and Alizarin heard mother comforting child, singing his favorite nonsense songs. Baby's responding coo interrupted the simple melody, managing to wreck the song and perfect it at the same moment. Alizarin's heart overflowed. I must keep them safe! At all costs! This was a battle worth fighting for, even if Gretsel didn't trust her or understand the immediacy of her danger.

Baby's cooing ceased.

Alizarin stood to knock. She would face her fear of rejection, she would protect her friend.

Under the doorway spiraled a cloying smell, of lit candles, burning wax and some undefinable scent. Softly at first, Alizarin heard a phrase being whispered. Each time the voice got slightly louder so that what was once soft and supplicating became a harsh and demanding tongue. Gretsel was praying? To whom?

The chant rose and fell in no particular pattern and the words were lost to translation. No God she had ever heard of. The sensual smell of the candles seemed heavy at first and soon became nauseous in its power.

Struggling to breathe, feeling oddly light-headed, Alizarin reached to her waist and untying her belt, she slipped on the cloak of her mother, placing it lightly over her shoulders. Gretsel was human, that she knew, but neither the incantation nor the incense that filled the doorway and the connecting hall were.

All around her, Alizarin could see twining strands of darkness rising, seeking. Whatever they were, they were wrapping around her body with a deceptive slowness, almost a cradle of peace-filled sleep. She could see them clearly, and she could hear Gretsel's voice droning onward in its urgency. Her friend acted to call some foul power remarkably similar in nature to the kind that Alizarin had just dispatched.

Horror seized her mind. What had Gretsel done? How did she know of these dark rituals, these words? What ill had she brought to the hearth of her family and friends? Indignation seared her heart. After all, who am I truly fighting?

Without knocking, without waiting any longer for the malevolent power of the tendrils to increase, Alizarin ran at the door with all of her might.

With a resounding bang, she fell. The door was well made and she was not a large woman. The chanting stopped for a split moment and then rose again, appealing.

Despite the pain now inflaming her shoulder, Alizarin was determined to enter, to stop the madness hidden within. Standing squarely in front of the doorway, she aimed low and to the side, kicking hard and strong.Crack! The door shivered but still stood.

Frustrated, taking aim again, Alizarin prepared to force her way into the locked room. Thinking that this was going to take a while at the rate she was going, she called out to the strange woman in the room whom she had thought she knew, “Gretsel, Gretsel, can you hear me? Gretsel, let me talk, please?”

Aiming her kick again, she thought to use her injured leg, as this attack of a barricaded room was looking to take multiple attempts. “Sister, please there must be some other way to safety, to escape!” She prepared to smash the door-hinge, as invisible vines of darkness covered her lower body.

With a grunt of displaced energy, her foot struck the unyielding door, with more power than she knew she had. With the bottom of the door kicked in, Alizarin could see into the room. Baby lay on the bed, asleep. Gretsel's back was to the door, and her incantation song did not cease. What had been a trickle of darkness spilling out under the sturdy door and into the hallway became a devastating flood. Alizarin's searching hands scrambled for her gemstones and their miraculous powers.

Lethargy set in.

Resolved to make another attempt on the remains of the doorway, Alizarin's thoughts slowed to a stupor. Her limbs felt heavy and tired. Her head spun. Clutching her purse with the two little stones inside of it, she ran at the doorway, falling more than striking. Waves of blackness swarmed her, blocking her breath, stealing her hearing. She could hear only a distinct buzzing sound, droning on.

Groggy, she collapsed onto the wooden floor, half in the room, falling.

The chanting voice continued.

Powerless against the immensity, the last thing Alizarin saw was the pure corruption, the non-reflecting abyss of Gretsel's eyes as she hurled a knife of pitch directly at her fallen friend's heart.

*

Within his gathering trance, within that moment of suspended breath, Ilion waited, supremely comfortable. He had no need to move for at least half a day. Then again, there was almost no chance of Alizarin taking that long to draw her innocent friend out of the empty farmhouse. Only a moment ago, the new mother's cries for the missing farmhands and her vanished husband had subsided enough that they

were no longer audible in the farmyard. Alizarin is already comforting her.

Surely, Alizarin would be able to explain what was in truth, even to his mind, almost unexplainable. She has a great deal of common sense, that one. I never was one to talk reasonably to irrational people, especially women. Ilion didn't handle the fears of others well. Gods knew he carried around enough of his own for the Circle Present. In his past experiences, women seemed to get super heated about absurdly small issues. Kalina had been easy to love and talk with, but when she had cried, he had never known which words would soothe or enrage her.

Striving to be kind and considerate, he more often than not felt like his words and intentions fit together like a block of sun-hardened brick clay attempting to cut bread. He regretted Kalina's inevitable departure but failed to see what he could have done differently to stop her. His mentor was fire, and he was ice. Then she was dead, slain by Jakor by all evidence. It was a death he would avenge when he returned to Dressarna.

Even in friendship, distance was more comfortable. Life is safer that way, safer to detach. He had learned that early on.

In his farthest, hazy childhood memories, he could still see the absurdly flying white hair and wizened face of the elderly priest of Bira who would come to visit the temple of Kira. Every planting season, like the deluge of the ready waterways with the burden of the melting snows, sure as sunrise, Ilion would see the old man's battered hat waving in the soft winds, his thin frame wrapped in brown robes. Even then, he seemed more of a twig than a man.

Only when the weary traveler reached the safety of the interior wall of Kira-Tang proper would he discard his outer, drab covering and reveal the inner power and intensity of the intricately embroidered, ordained crimson priestcloth. Since his earliest awareness of the seasons and their cycles, Ilion had always looked forward to the old man's coming.

Into the Raging Mountains

Into the Raging Mountains